Photography: Beyond the Surface:

Opening reception: 4-6 p.m. Saturday, (November 9, 2019)

Exhibition runs: Nov. 9 - Jan. 12

Address: 665 W Lancaster Blvd, Lancaster, CA 93534

Solo exhibitions: Matthew Finley, Rob Grad, John Peralta, Melanie Pullen, Christopher Russell, Joni Sternbach, Rodrigo Valenzuela, and a site-specific installation by Kira Vollman. Selections from the Permanent Collection are also included in the exhibition.

Christopher Russell is a writer and visual artist. He uses photographic images as a basis for mixed-media works and installations. He received his MFA from the Art Center College of Design, and has had a solo exhibition at the Hammer Museum.

Christopher is in the upcoming show at MOAH, the Museum of Art and History, titled Photography: Beyond the Surface. A former Los Angeles resident, Christopher now lives in Washington state.

Tell us about the work you have in the upcoming show at MOAH:

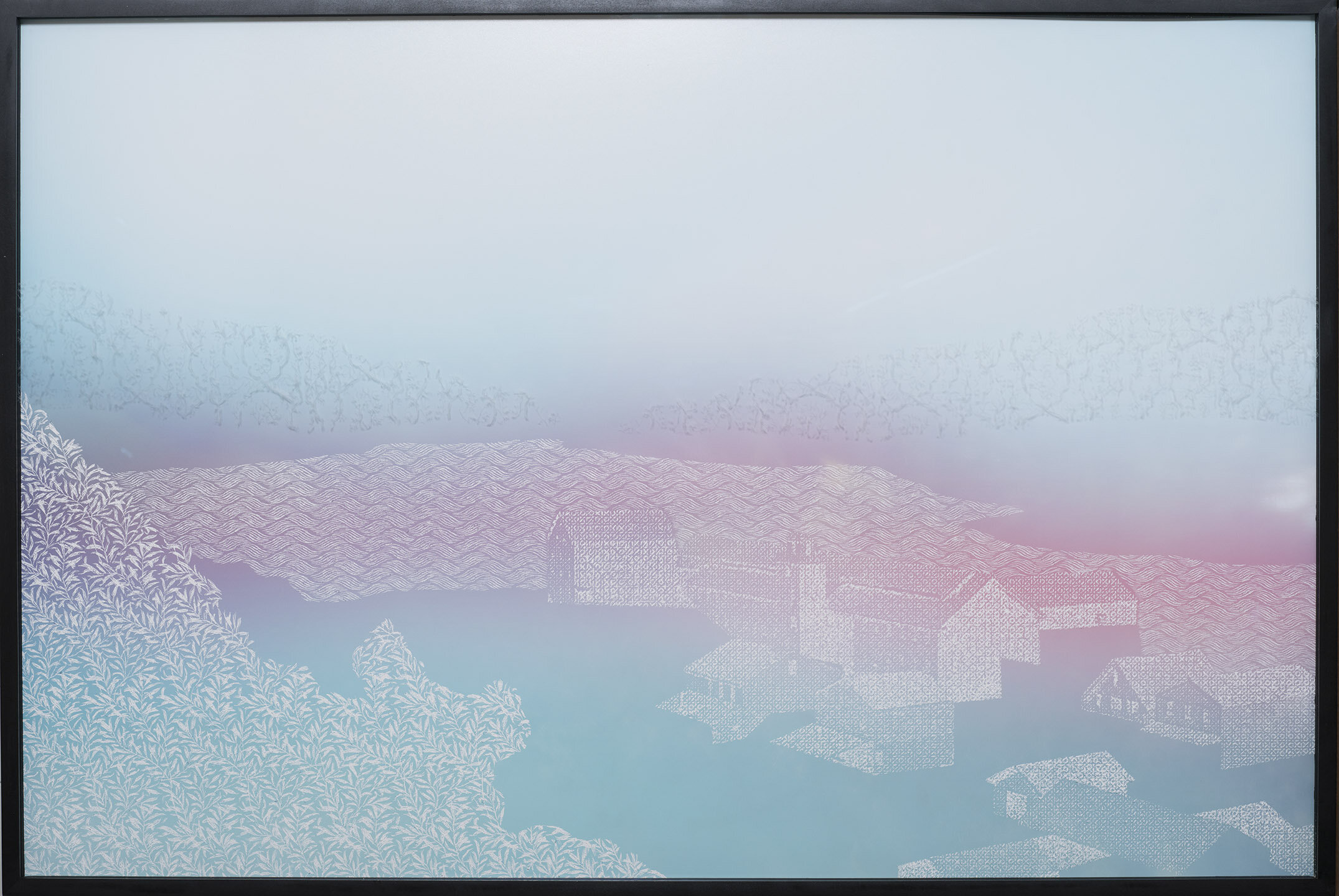

The work comes from time I spent living in Portland, Oregon, and ideas that I’ve been developing around the death of photography. Essentially, the predominance of digital images has shifted the societal understanding of what a photograph is, disrupting the foundational understanding of the photographic process: the perceived truth of its illusionistic image. Most of what is now produced and called photography comes from a process that privileges the malleability of images; it has a different foundational aim.

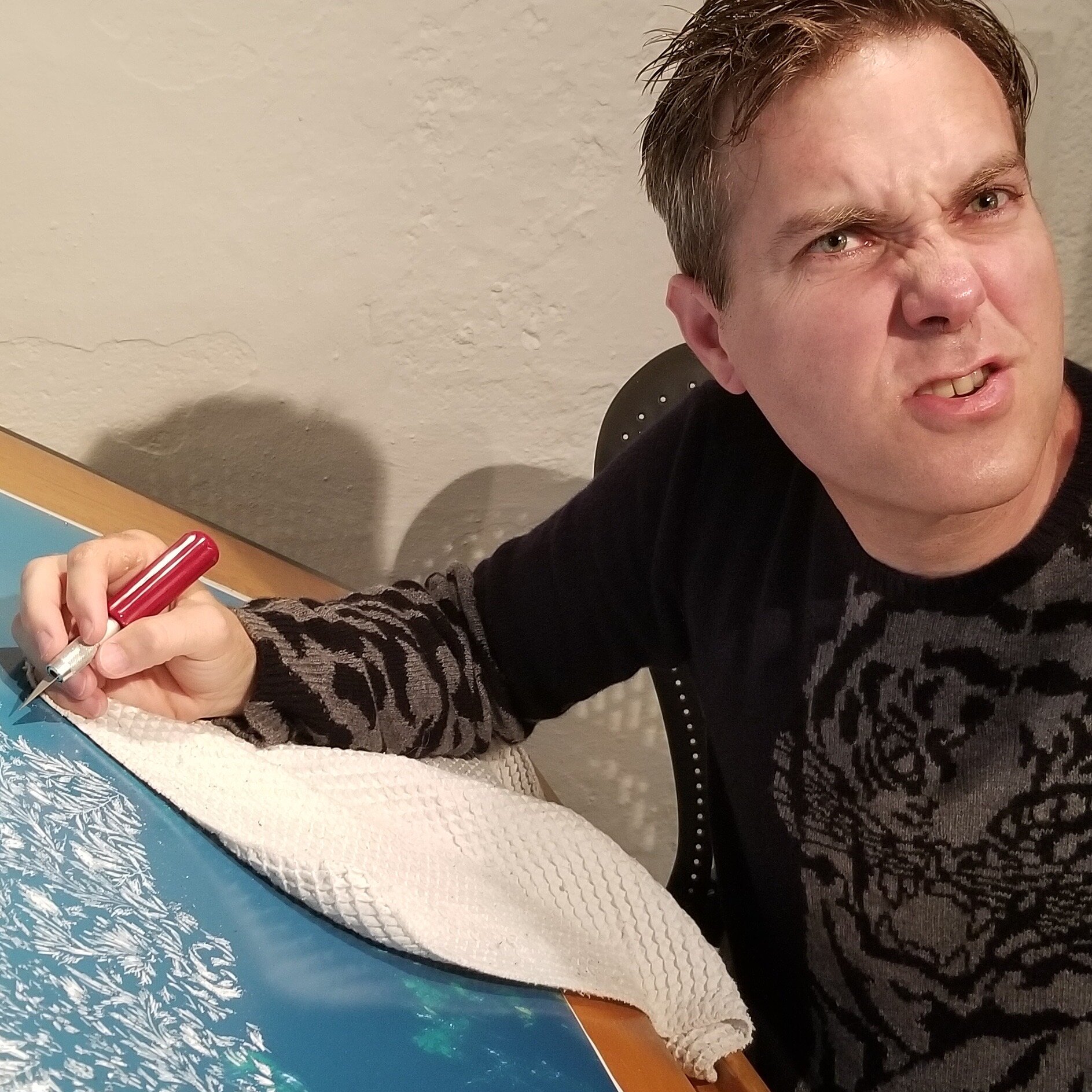

While photographing in the Columbia Gorge, I realized that I was operating on the opposite end of photography’s historical continuum. I was looking at more or less the same geography as Carleton Watkins, who photographed the same space in the 1860s, but our aims couldn’t have been more different. He was a documentarian who worked in partnership with the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, while I am unabashedly Romantic, and my move to Portland was a first step toward a more reclusive life. Watkins images were tack sharp, and his compositions helped define the popular conception of The West, while I throw fabric over the lens of my camera, and scratch into the resulting prints.

There was no record of Watkins’ daily life on the Columbia Gorge expedition, so I decided to write it: a travelogue written in the spirit of a photographic process that was designed for manipulation and consequently embraces fiction. The book in this exhibition is the first section of a larger text. It details the first leg of Watkins’ journey: the boat ride from San Francisco and his trip to Willamette Falls. The images in the exhibition are all waterfalls. Sometimes that is represented simply by a break in pattern, sometimes it’s an attempt to make the paper appear to cascade from its substrate.

Why did you take up photography as your main visual art medium?

I came to photography in the mid 1990s. I was drawn to the process, the ability to record reasonably accurate shapes and tones from the world around me. I was immediately taken by photography as a medium of surveillance. There have been lots of shifts in focus, like writing and bookmaking, but those other activities have always been informed by a conceptual relationship to photography.

You are both a writer and visual artist. Do the two artistic mediums build on each other, or do they compete for your time?

Yes. The two both build upon and compete with each other. My work exhibits primarily in a visual art context, so I think most people assume the writing is subordinate, or perhaps even superfluous—when it’s even noticed at all. For me, the tension between the two is productive. The work on the walls of the exhibition, the “waterfalls,” are a response to a challenge posed by the text. There is a lovelorn Watkins whose opinions become, sometimes, too clear. Then there is the object of his affection who is only known to the reader through Watkins descriptions. The third main character is Bigfoot, who exists primarily through forensics: footprints, hairs caught on a log, or a gift delivered while Watkins sleeps. Much like a photographic portrait, two of the main characters are established from a distance, their interiority is revealed through a relationship with somebody else. For me, the next set of questions is how one might create a similar dynamic of distance and presence within a visual work. So making the images became a process of trying to find material metaphors for “waterfall.”

How does nature inspire your art? Do you ever find inspiration in the desert landscape?

Nature is counter culture. Every aspect of society is set up to create a separation between man and nature. It’s why we can’t begin to to truly combat the climate crisis, nature, the actuality of nature—not the myriad symbols that evoke it—has been othered to the point that it holds virtually no cultural significance.

When you’re in nature, it’s perverse, scary, lonely. There is a place I visit near my home in Northeastern Washington State that is defined by lichen covered basaltic knolls within a field of yellowed grass that surrounds an ever-choppy, lead colored lake. In an instant this scene delivers all the drama of Wuthering Heights. It’s a type of beauty that is physically exhausting. It’s perhaps a better connection to the ideas of Kant or Friedrich than reading or viewing their work.

The desert is amazing, I remember these waddling miniature dinosaurs that shoot blood from their eyes from my time in Southern California. (Horned toads.) But I really can’t handle the heat, and that’s a major factor in my recent succession of northward moves.

What tips do you have for people photographing nature?

There is no other goal than the pursuit of radical reinvention.